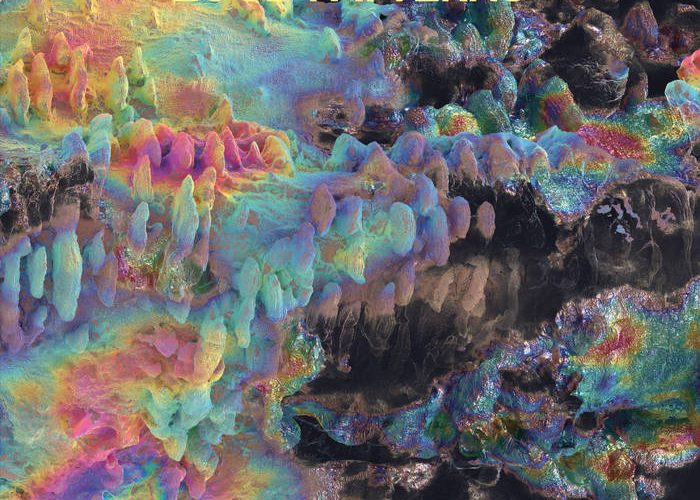

In his debut album, producer Makeness (Ryan Molleson) manages to be satisfyingly weird, yet maintains a grounded edge to his work. Part of that success of balancing his style between the strange and the familiar is Makeness’ ability to know when to pull back. Rather than fill every nook and cranny of Loud Patterns with more advanced, busy sounds, about half of the time on instrumental tracks it is more subdued with just drum and bass and occasionally one other instrument. It really puts the rest of the album in perspective and gives a lot of clarity to the dense parts.

While this album does not have frequent vocals, and very few after the first half, the vocals on every track are treated with care and respect. I find that in a lot of music, especially weirder electronic music like this, vocals are used as more of their own instrument rather than the star of the show, accomplished by drowning the vocals in layers of effects and burying them deeper in the mix. The vocals on Loud Patterns aren’t necessarily effect-free, but they are still given their moment to shine, and they certainly do. The bass on this album is consistently great, with a lot of fuzzy tones that keep the songs in motion in the more stripped-down sections.

This album could have started out much stronger by leading with its more straightforward tracks. “Loud Patterns,” the title and lead-off track, certainly lives up to its name, using downright noisy feedback and synths, and “Fire Behind the Two Louis,” the track that follows, has some extremely squiggly synths. Both aren’t the strangest tracks on this record, but are certainly harder to enjoy on the surface level than the two singles, which puts a bit of a kibosh to the idea of a slow descent away from reality. In a press release for his label Secretly Canadian, Molleson said that “”Stepping Out of Sync’ for me is a bit about losing a little bit of a grip on reality.” This idea is easily applicable not only to that single, but the album as a whole, and that trip out of reality would be much smoother if we were introduced to the more familiar elements first. The album ends somewhat disappointingly, with the final track, “Motorcycle Idling,” being literally a recreation of a motorcycle idling, using drums and bass. Imagine the beginning of Van Halen’s “Hot for Teacher,” but it goes on for three minutes and there’s no Van Halen afterwards.

Overall, this album provides a unique blend of dance music made by weird people and abstract experiment electronic music made by even weirder people, with a nice sprinkling of pop thrown in to boot, but fizzles out when it could have truly exploded at the end.

-Joseph Mullen