Scattered across the North campus of the University of Georgia are markers detailing the defining moments in the history of the university’s founding. A marker by the Old College talks about the transformation of UGA’s first building over 200 years. Another at Herty Field tells the account of UGA’s very first football game against Mercer, which was also the first football game ever held in the state of Georgia.

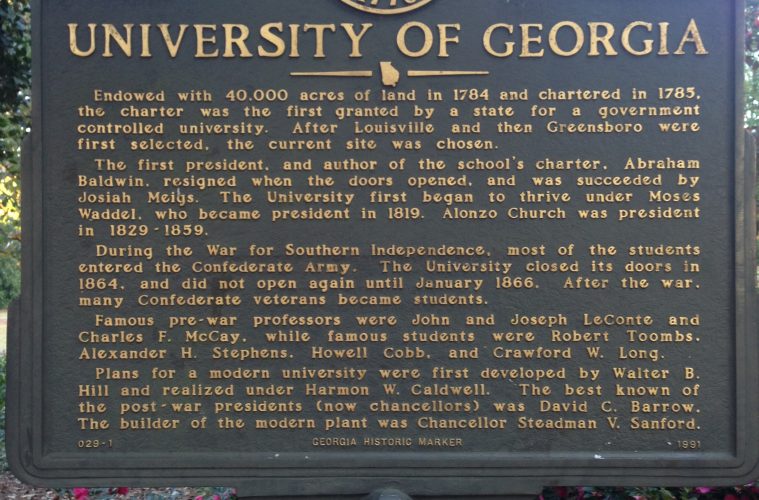

And on the historical marker right beside the Arch, the story of the founding of the University of Georgia and influential men who held the university presidency is told. But when the story gets to what happened to the university during the Civil War, it refers to that war by a name that’s probably not known by many – the War for Southern Independence.

John Neff, a Civil War historian and professor at the University of Mississippi, said that he’s not sure where the term, “War for Southern Independence” first originated. But he said it was phrase solely used by members of the Confederacy during the Civil War, and supporters of the Confederacy after the war.

“I think that term has to be considered particularly during the War, and even after, a purely Southern term,” said Neff. “The North would never have embraced such a term.”

The Georgia Historical Society is the non-profit organization responsible for putting up and maintaining historical markers across the state. Stan Deaton, senior historian at the Georgia Historical Society, said the marker by the Arch was originally erected in the 1950s, and a replacement was put up in 1991 – but no wording was changed on the replacement. He said white confederates used the term “War for Southern Independence” to hearken back to the American Revolution, which they saw as the “War for American Independence.”

“So in the early 1950s when this marker was put up, that would have been a term most white Southerners would have agreed with, and would have used. Most of them would not have used the term, “Civil War,” probably,” said Deaton. “But this [term] is the one the state of Georgia, probably with the agreement of professors at Georgia, would have agreed with. That’s probably how it wound up on there in the first place.”

The War for Southern Independence is not the only term that carries with it a politically loaded interpretation of the Civil War. After the War, Congress officially used the term “War of the Rebellion” in all references to the War as a way to frame the Southerners as rebels against the U.S. government.

Three other terms were used by Southerners – the “War Between the States,” which emphasizes the issue of state’s rights. The “Late Unpleasantness,” was also used, though not very widely, to avoid any reference to the War and not acknowledge that the South lost. The “War of Northern Aggression,” was also used, and framed the Union as the cause and aggressors of the War.

These interpretations of the Civil War are still held by James King, a member of the Georgia chapter of the organization, Sons of Confederate Veterans.

“It was not a Civil War technically. That’s an inaccurate term that’s been applied to it and it’s commonly accepted by most everybody these days,” said King. “The South did not fight to gain control of the U.S. government in Washington, D.C. We fought for state’s rights to form an independent nation, just like we did in the Revolutionary War… Technically it’s more appropriate, to call it a War for the Southern Independence, because that’s what we were doing.”

But, Neff, the University of Mississippi historian, said the issue of state’s rights as a cause of the Civil War cannot be separated from the issue of slavery.

“The two are linked. You can’t really have one without the other. The independence movement, the secession movement, was really about preserving slavery as the engine of the Southern economy,” said Neff.

Neff said this can be proven by looking at documents that Confederate states filed when they decided to secede from the United States. In Mississippi’s Declaration of Secession, the state directly said, “Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery – the greatest material interest of the world.”

Deaton said the term War for Southern Independence is outdated, and would not be used on any of the new historical markers that the Georgia Historical Society puts up today.

“Someone wrote that marker and tried to tell UGA’s story through the lens of the confederacy,” said Deaton. “We would all agree that this is a poor marker if it’s trying to tell the history of the University of Georgia.”

Knowa Johnson, the co-founder and vice president of the Athens Anti-Discrimination Movement, believes students and faculty at UGA should rally around changing the wording on the historical marker.

“It is a statement that the University would put that there. That was a long time after the Civil War. To put something there that supports the lost cause, it says a lot about the history that they’re trying to uphold,” said Johnson. “I understand there is a large Confederate history at the University… but I think it should be a movement that takes place on campus to change the sign and put something up that puts it in the true context of real history, and not just one-sided point of view.”

But changing the sign may not be that easy. Deaton said that’s because of a complicated history with the historical marker program.

According to Deaton, the Georgia Department of Natural Resources had control of the historical marker program until 1997, and it was funded through the state legislature. But in 1997, the state of Georgia decided it no longer wanted to fund the historical marker program. The Georgia Historical Society did not want to see the historical marker program disappear, so they approached the legislature, and asked if their organization could receive money from the state to maintain the program. Their request was granted.

So, any markers put up after 1997 are owned by the Georgia Historical Society. But signs put up before 1997 are still owned by the state – like the historical marker by the Arch. The Georgia Historical Society is responsible for maintaining these signs, but Deaton says that only means the physical upkeep of the sign. It does not include any control over changing signs or sign language. That would have to come from the state.

“These pre-1997 markers are basically orphans, because they’re in this no-man’s land. The state owns them and we maintain them. But you’ll be hard-pressed to find anyone at the state who will take responsibility for them,” said Deaton. “But if the state were to claim the signs, we recommend that they follow what we do and put up a sign that includes more broad and inclusive stories.”

Greg Trevor, spokesperson for the University of Georgia, told WUOG in a statement that the sign is not the property of the University of Georgia, but is owned by the state of Georgia. No further comment was given about changing the wording of the sign.

By Victoria Knight

Source List:

Dr. John R. Neff

Associate Professor of History and Director of the Center for Civil War Research

University of Mississippi

(662) 915-3969

Dr. Stan Deaton

Senior Historian

Georgia Historical Society

(912) 651-2125

James King

Commander SCV Camp 141 Lt. Col Thomas M. Nelson’s Rangers

Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV)

(229) 854-1944

jkingantiquearms@bellsouth.net

Knowa Johnson

Co-Founder and Vice President

Athens Anti-Discrimination Movement

(678) 740-3884

Greg Trevor

Executive Director for Media Communications

University of Georgia – Office of Marketing and Communications

(706) 542-8090